A GUIDED TOUR THROUGH TWELVE YEARS

OF AMERICAN MUSIC IN ROME

St. Paul's Within the Walls. Photo George P. Landow

St. Paul's Within the Walls. Photo George P. Landow

During one of our last meetings at Yale, Mel Powell said, "Sure, you'll go over there, wear a beret, write a far-out piece, and come back and get a teaching job here." The only part of this prophesy that came true was my going to Europe; I don't think I even got to writing a far-out piece.

I have been living in Rome since December 1964 when Joel Chadabe and I, together with the violinist Joan Kalisch, arrived here from Berlin, where Joel and I had been guests of the Ford Foundation and students of Elliott Carter's for a year. This was all part of some political plan to regenerate the cultural life of the city – an international showcase idea which went along with lots of neon signs and skyscrapers – to shout down communism. Most of us felt as if we were on the moon. I had never been so far from the sea in my whole life. However fresh out of Yale and carefree we were, it was all disconcerting, just the same. A great part of that year went into drinking beer and dreaming about Italy. Joel had been there the year before and convinced me of Rome's life-giving properties; besides, it sounded like the perfect place to thaw out our unsettling Berlin experience. There was no hesitation. Our grant terminated, we drove straight to Rome, where we would finally begin "becoming" composers.

I knew very little about music then and even less about the world around me. Rome was an impenetrable mystery. I had a little prize money to live on for a year. So in this state of blissful ignorance and isolation I set out to compose music; not knowing why, what or for whom, but simply believing that I had to and that maybe someday there would be a real need for this stuff. For those of us with no experience outside of central heating for keeping warm, you must be a martyr to want to compose music in mid winter in Rome – it's freezing. In any case I got going on a piano piece in which I did everything I was never allowed to do. FIRST PIANO PIECE (CPE editions) starts off like Art Tatum gone mad – finally, a clean break from my student years. I was really proud of this work. Its very existence seemed to be reason enough to continue composing. With it too, I overcame the lethargy which pervades all newcomers to this city.

|

|

Joel Chadabe |

Giacinto Scelsi |

It was a lively first year, though. Besides Joel Chadabe and Larry Moss whom I saw frequently, my old friend from Yale, Richard Teitelbaum, was here on a Fulbright to study with Petrassi, as was Cornelius Cardew whom I got to know well. New music was far from lacking in Rome in those years. The weekly RAI Radio Orchestra concerts very often had new works. And that season, the ailing Bruno Maderna conducted Carter's Double Concerto with Frederic Rzewski on piano and Mariolina de Roberti on harpsichord. The second meeting place for the new music public was the American Academy where that year John Eaton presented music performed on one of the world's first synthesizers, the SYNKET, created by the affable Italo-Russian, Paul Ketoff. There I heard the soprano Michiko Hirayama, a singular performer who has contributed greatly to many new music developments in this city. The Academy over the years has tried to correct its rather isolated position. Much was done in this direction by Bill Smith who found a warm acceptance for his experimental clarinet playing as well as for his jazz and commercial music. On one of the Academy concerts he, together with Joan Kalisch and Cardew, performed a trio of mine. The most important and lively concerts, however, were the NUOVA CONSONANZA series, organized largely by Franco Evangelisti. Evangelisti proudly announced that he had stopped writing music, as if the gesture itself was the farthest out piece one could write. In any case he has continued as a prime mover on the Italian music scene, which was then entering "middle age" and becoming acutely aware of having exhausted the Webern legacy. There was also a generally widespread feeling that concert music was in trouble, and perhaps that was not the fault of the public alone. That season NUOVA CONSONANZA programmed a rather disappointing version of Roger Reynold's EMPEROR OF ICE CREAM, Cardew played George Brecht (also in Rome at the time), and Bill Smith played his elegant solo clarinet pieces with ring-modulated-sounding double and triple stops. Giuseppe Chiari was also on hand to do his amusing piano antics. And through the energetic conductor Daniele Paris, Rome was becoming aware of the music of Charles Ives.

Joan left for America and I moved to Fritz Kraber's house in Piazza Navona, and as my funds were dwindling I began to play cocktail piano in bars on Via Veneto. The work was short lived when I accepted an offer from the harmonica virtuoso John Sebastian (father of the pop star of the same name) to become his accompanist on a two-month tour in Africa. This was a timely and unforgettable adventure. It gave me time to reflect on the confusing musical life that I was preparing to enter, and at the same time brought me into the world of political meanings for the first time. After I returned to Rome, Edith Schloss, an American painter, was about to have a show of watercolors at the American Church in Rome. She thought it would be nice to have sounds with the show; so with a borrowed Uher I went all around the city collecting sounds of water: drains, fountains, toilets, baths, faucets, etc. I mixed 45 minutes of this, collaging it with Handel and the Beatles, in the studio of the American Academy. Titled WATERCOLOR MUSIC, this piece plus Edith's show became occasion for a concert in which Jerome Rosen, Jed Curtis, Alan Bryant, and myself performed.

Alvin Curran with John Sebastian Sr and his wife Gitte, Yaounde, Cameroon

In the spring of that year (1966) Frederic Rzewski returned to Rome after a term in Buffalo. We had known each other in Berlin but were rather distant musically, as I was still a nobody and he an already overworked avantgarde pianist. Frederic was full of the most incredible ideas and visions (often contradictory); he set out dauntlessly to realize them one by one. In that moment he was into electronics and had brought back with him some cheap contact mikes and Lafayette mixers, plus some discarded circuitry of David Behrman’s. Together with the American musicians Alan Bryant (then with the primitive makings of a synthesizer), Carol Plantamura (voice), Jon Phetteplace (cello), and the Italian Ivan Vandor (sax), we hooked up a lot of junk, springs, glass plates, rubberbands, buzzers, and whatever else was at hand and began like ecstatic children to wander far and wide in this magical and seemingly unending world of improvisation. It was like discovering music for the first time. I began playing a discarded trumpet that was lying around, began singing as well. Each of us reveled in discovery of his own inner music -- the source itself. And "harmonizing" with the others became like a drug experience, demanding ever more fluency and intensity. From the beginning of these sessions, there was an awareness that we were dealing with something very serious – very fundamental. Larry Austin was in Rome then and we listened to tapes of the Davis Improvisation Ensemble. They were very professional sounding, I remember, seemed to favor a "pieces" orientation and scorned "mistakes." Around the same time Cardew formed the AMM group in London – improvisation had clearly burst onto the scene. My own dreams of becoming a composer began to fade as I was swept into this all-consuming whirlwind of instant music making. The word "composer," however, took on a new meaning now that there was a possibility to compose for something, i.e. a group of people like myself, who were searching for an alternative to the bourgeois social and economic prospects we had been unquestionably headed for. MEV (MUSICA ELETTRONICA VIVA) was born.

MEV in the Kitchen, Mercer St.

The years 1966 and 1967 witnessed a flurry of autonomous activity on the part of MEV, notably two small festivals, AVANGUARDIA MUSICALE I and II, largely organized by the group and sponsored by the private concert society L'ACCADEMIA FILARMONICA ROMANA. Apart from our own works, these concerts presented a wide selection of first European performances of music by Mike Sahl, Kosughi, Feldman, Cage, Gelmetti, and Chiari; the whole Sonic Arts Ensemble (Union) performing Behrman's RUNTHROUGH; Ashley's FROGS, and Lucier's brainwave piece MUSIC FOR SOLO PERFORMER 1965. Of note among the MEV works was Alan Bryant's QUADRUPLE PLAY for amplified rubberbands. The NUOVA CONSONANZA Improvisation Ensemble, a ray of light on the arid Italian scene, was heard for the first time in elegant, almost "studied" improvisations. In the middle of all this Charlotte Moorman and Nam June Paik turned up – Charlotte insisted she wanted to do a performance for the Pope – and did a memorable show complete with propellers on her breasts and immersed in an oil drum filled with water, all at the Feltrinelli bookstore, latter the scene of Rome's first "happening." For that occasion Frederic, with the technical help of our friend Clyde Steiner, gave a first performance of PORTRAIT, an unusually integrated play of sound and shadow performed by Carol Plantamura, who nude behind a shaped screen, commanded a primitive but efficient photocell-light mixer with her body movements as she sang. Ever further on the foreign "fringe" but with an increasing following, MEV organized two other big concerts. One was with Larry Austin in which he introduced us to a four channel tape in ACCIDENTS. On the same program was David Reck's NIGHT SOUNDS AND DREAM, a beautiful piece (I later had the pleasure of meeting Reck when he appeared in Rome as a vinah player in a concert of Indian music), and my work, LA LISTA DEL GIORNO, where Barbara Mayfield cooked hamburgers to a background of taped kitchen sounds, recipes, and a trio of Te Dansant musicians. At the other concert, given at the American Church, we organized some 25 friends who performed choral works by Bryant, Rzewski, Gelmetti, and myself, all written for the occasion. The choral form seemed to bring out the best in each of us as we presented very diverse but extremely memorable pieces. It was as if we had reached a milestone and once there wanted to say farewell to written music for a while. Giuseppe Chiari was also in this concert, as both he and Gelmetti were closely associated with MEV in those years. Chiari made music out of anything commonplace: words, thoughts, objects, sounds (heard or imagined); and Gelmetti, already famous for his electronic music for Antonioni's "The Red Desert," was a very skilled collagist with a great sense of humor. By banding together with these Italian "rebels," our disassociation from the official music world became total.

It was a crucial time, the winter of 1967. To survive the group needed its own place to pool its collective resources, material and creative, so to assure the survival of its budding revolutionary mission. We finally found an old damp soot-covered foundry in Trastevere, took up a collection, and with the money fixed the place up, learning the hard way about cement. Richard Teitelbaum had just come back, and brought with him the first Moog synthesizer to be seen in Europe. Meanwhile Alan Bryant, who taught himself electronics out of do-it-yourself books, had built his own synthesizer – which looked like some Rube Goldberg contraption, with hundreds of banana plugs and wires coming out on all sides. Bryant kept this aluminum column in a plastic bag. To these diabolical machines we added our unique collection of oil drums (contact mike-amplified), tin cans, thumb piano, glass plates, springs, aluminum tubes, chimes, cymbals, sax and cello. One can imagine what the MEV "sound" was like in those days.

Fredric Rzewski - Richard Teitelbaum - Ivan Vandor (photos Gerd Conradt)

For two years the MEV studio became the scene of an intense musical and social (political) struggle, which took place on many levels. The individual and the collective were pitted against one another – any of us who still harbored ideas of being composers had to compose quietly on the side. The exclusion of non-group members from playing gradually became taboo itself. At first only musicians were admitted to sit in: finally, "non-musicians," wives, and children were let in. In a still later stage, the whole audience was invited to participate. So in the fall of 1967 the MEV studio, to the amazement of its own members, opened the door to whoever wanted to play. And night after night crowds of people came in to play or to listen to this overwhelming, continuous music, which could have easily been the accompaniment to some tribal ritual – a ritual of initiation and preparation. In fact, it was. And the ritual was simply the social upheaval and related phenomena that was then beginning to manifest itself everywhere, West and East.

We lived from month to month, mouth to mouth, concert to concert, always dreaming of a communal life where giving and receiving no longer would be self-conscious acts. The LIVING THEATRE, who were operating in Italy in those years, became the heroes of the evolving young people here -- their message was felt everywhere. At the same time Eastern Philosophy, yoga, drugs, and even Scientology had all burst onto the scene. Rome, all of Italy, and for that matter much of Western Europe, was shaken out of its complacent middle-class-postwar dream. Students, anarchists, hippies began to fill up the prisons. MEV was right in the midst of this but, like most musicians, preferred to stay out of the front lines. Our concession to the "revolution" was to take in two non-musicians (Cataldi and Coaquette, who had no degrees from Harvard or Yale) and one extraordinary jazz musician, Steve Lacy. MEV became a school and everybody learned from everybody else.

Garrett List, Frederic, Steve Lacy at Via dell'Orso

By 1969 we had played all over Europe and were known to everyone for our unusual social constitution, adaptability to any situation, and our sublime or terrifying improvisations. It was a period when everyone was everything – the public could no longer be held back. Finally, SOUNDPOOL was created as a performance where the public was invited to bring a "sound" and cast it in with us. It was the hardest music we ever attempted to make, but often led to moments of unbelievable harmony and intensity. To my memory no one was ever physically injured, but we did keep records of one indoor fire (University of Louvain), several broken chairs, and an uprooted potted palm in the Purcell Room in London. In spite of the din, a lot of good human feeling was always brought out. These "concerts" often left people wandering around lost, in a daze, in spent ecstasy, quiet. All having unleashed some dormant and powerful energies, having liquidated the imaginary enemies, having felt together, united with the others, having felt free – having won the battle for survival.

MEV at Via dell'Orso, photo R. Masotti

During all of these developments I continued composing, but in a way I never would have imagined before. My interest in natural sounds and recording was directed toward the creation of a 70-minute tape piece, A DAY IN THE COUNTRY, which is a kind of "soundscape" freely based on the structure of an imaginary day. I also began composing simple melodies – long monophonic pieces which lent themselves to rather free polyphonic interpretations. Of these, MADONNA AND CHILD and UNDER THE FIG TREE were performed a lot. About 50 of these works are included in my collection MUSIC FOR EVERY OCCASION (Experimental Music Catalogue, London).

|

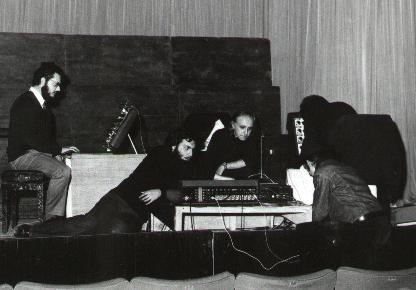

AC with Domenico Guaccero, G. Mazzuca, S. Rendine |

In MEV's last period in Europe, the group itself returned to performing individual pieces, and created an organic presentation by overlapping one with the other. Often combined were Richard Teitelbaum and Barbara Mayfield's IN TUNE for amplified brainwaves and Moog Synthesizer, Rzewski's LES MOUTONS DE PANURGE, my ROUNDS, and Christian Wolff's STICKS. The latter, where we furnished lots of wood and whole branches of small trees, served as a transition to SOUNDPOOL with the public. This was our basic program for a tour we did in the USA in 1970. Americans had no hangups about participation; on the other hand, their politics was less evolved than that of European students. But whatever their individual qualities, neither group had trouble letting go with MEV. Later during the same tour the group was joined by the stimulating presence and sounds of Maryanne Amacher and Anthony Braxton. In recent years in NYC Gary List and Gregory Reeve had become permanent members of the group, with frequent participation by Karl Berger and Jon Gibson as well.

|

|

Anthony Braxton, photo Leandre Jackson |

Jon Gibson in Kounellis sculpture |

That year (1970) both Teitelbaum and Rzewski had decided to return to America; I decided to stay in Europe, but MEV in Rome was over. The 1968 "revolution" was history. Everywhere people were trying to piece together the meaning of that rush of experience. "Is it an end or a beginning?" No one knew.

I continued on the wave MEV had created and formed MEV2 – a group of usually 6 European "non-musicians." Though this experiment proved that it could be done and even showed great promise, the group did not have the will to survive longer than one year.

Among the most interesting music heard in Rome in this epoch was on the concerts organized at Fabio Sargentini’s avantgarde gallery, L'ATTICO. MEV together with the dancer-singer Simone Forti and the painter Michelangelo Pistoletto collaborated in the first of these events, which goes back to 1968. Dating from 1969, with the appearance of Terry Riley and La Monte Young and Marian Zazeela, these spring festivals became regular for several years and one by one the whole Soho music and dance bandwagon passed through or stayed for brief periods. These annual encounters with Glass, Reich, Palestine, Forti, Jonas, and Reiner became for me, apart from seeing old friends, a kind of booster shot of American and specifically New York energy, and signaled the direction of creating solo performances which I would soon take up.

Philip Glass ensemble 1971 |

Simone Forti frame from "Senza Titolo" |

This happened in 1973. Tying together all the bits and pieces of my past experiences, I produced CANTI E VEDUTE DEL GIARDINO MAGNETICO (Songs and Views from the Magnetic Garden), an hour-and-a-half piece for tape, voice, flugelhorn, and synthesizer in which I develop three melodies over a slowly evolving recorded "soundscape." GIARDINO MAGNETICO was performed for 10 consecutive nights at the Beat 72, Rome's cradle of the avantgarde. I continued this format in FIORI CHIARI FIORI OSCURI (Light Flowers, Dark Flowers) for ocarina, voice, piano, toy piano, synthesizer, and tape (1974-5), as well as in LIBRI D'ARMONIA (Harmony Books) for conch shell, zither, voice, piano, synthi, and tape (1975-6). These performances seemed to speak directly to the ever growing new-music public here, whose response encouraged me to go in this direction and permitted me to live from my work. So, from the individual, to the collective, to the individual again.

Now I am teaching from my MEV experiences at the Academy of Dramatic Arts, and new collective pieces are brewing again. Italy is at the crossroads, about to make a crucial choice. People want human life organized on a human basis. Frederic is back, and Teitelbaum is threatening to come over – e allora? Gary List is organizing MEV concerts in the USA again, so any occasion is a good one to get together and play – after all, that's what MEV is all about.

No account of American music in Rome would be complete without mentioning a number of Americans who have been independently active here for a long time: Richard Trythall has been associated with the American Academy these last years, and largely responsible for revitalizing the musical life there, and especially for bringing the Academy in closer touch with musicians in the city itself. He's written many chamber works, but as a tape-freak Trythall has produced memorable work in collaboration with the visual machinery of Milton Cohen. James Dashow is an electronic purist and creates many elegant chamber compositions for tape and live performers, often played by his group THE FORUM PLAYERS, in which the soprano Joan Heineman, also active at the American Academy, is dedicated to tape music as well. His works have a very personal touch in using everyday sounds that often tend toward irony in a context of music-theater. Roberto Laneri, an Italian schooled in the US at Buffalo and San Diego, is now one of the most active musicians here; his group PRIMA MATERIA is a very unusual vocal improvisation outfit dedicated to the search for universal harmony. Laneri is also, together with guitarist-composer Tony Ackerman, one of the prime movers of the jazz-oriented SUONOSFERA group. Closely associated with all of these people is the new music performance group NUOVE FORME SONORE led by trombonist Giancarlo Schiaffini and Michiko Hirayama, with whom American Academy fellow William Hellerman often collaborated as composer-guitarist. MEV, myself, and nearly all of these people mentioned have been closely followed, criticized, chided, and encouraged by a single person, 70-year-old composer Giacinto Scelsi, whose extraordinary works have been a singular source of inspiration to all of us. Recently Scelsi, Laneri and myself have formed a cooperative, ANANDA, for the publication of recordings of our own music and that of other composers with similar interests. A first series should be available in September 1976.

This is of course a biased report. After all it's my "guided tour." I regret having skimmed over the Italian music scene, but that was not my intent. Surely I've left out a lot of events – two of them come to mind now: a big happening in which John Cage entertained the whole Roman intelligentsia by cooking pepperoni for them, and Morton Feldman's meteoric rise to fame in Rome around 1970. Americans passing through here often say "...but nothing ever happens in Rome." Yet most of what I have described has gone on here under no grants, no foundations, and under no one's auspices other than our own. Perhaps because this activity was the product of an autonomous foreign community, immune from the innate diseases, intrigues, and bureaucratic tangles which afflict Italian musical life, it continued to survive on its own vitality and that of the people who made and supported it.

ALVIN CURRAN, Rome, June 1976.

published in Soundings No. 10, Soundings Press, Santa Fe, 1976.