Reflections Of An American Composer

In The Late Twentieth Century (excerpt)

East West North South Tonal Atonal Analog Epilogue Dialogue Digital Order Chaos

Notated Improvised Coded Encoded Welltempered Distempered Harmonic Series World

Series Free Aggregate Closed Cosmic Solar Lunar Urban Suburban Minimal Maximal

Post Trans National Global Universal Local Mythological Microbal Macroevolutionary

Fractal Viral Semiotic Ontologic Static Dynamic Dada Dado Dea Deus Druid Dravidian

Appolonian Dyonisian Form Content Collage Assemblage Implosive Explosive Tranquil

Steady-StateTurbulent Meltdown In-Time On-Time Beyond-Time Before-Time Aztec

Biblical Heiroglyphic Sumerian Hebraic Paleolithic Monogenesis Identity Uncertainty

Mesoamerican Protoindoeuropean Postcontrapuntal Tribal Multitracked Periodic

Lyric Entropic Programmed Aperiodic Systemic Linear Random Lydian Cyclical Cretan

Fragmented Unending Flowing Hocketed Repeated Additive Subtractive Timbral Spectral

Phased Feedback Set Reset Fission Fusion Fibonacci Golden Mean l9-Tone Golden

Arched Noah's Arc Trajan's Arch Neobalkanized Hypertextual MetaRomantic Retro

Virtual Transcendental Accidental Fascist Metaphor Socialist Paradigm Democratic

Parable Anarchic Alchemical Agnostic Androgynous Lingual Glottal Gagaku Gulag

Babel Gulasch Beethoven Bach Josquin Thelonius Tibetan Stochastic Genetic Environmental

Evangelical Erotic Sweet Sour Painful Equilibrium Bondage Pathological Biodegradable

Cellular Luminous Purgative Continuum Persian Coptic Ukrainian Ugandan Ur Amargeddon

Aboriginal Bebop Zydeco Hip-Hop Doo-Wop Dravidian Mongolian Argentinian Polish

Electronic Heaven Hell Metal Mystical Georgian Jurassic Chance Cuban Quatsch

Silent. These are our themes -- drawn like water from a common well; these are

the compositions that everyone everywhere writes in their dreams, the rich broth

that we nourish ourselves with: THIS IS THE NEW COMMON PRACTICE -- The 21st

century Theme Park.

While

only a short generic list, this is a kind of beginner's guide (for surely it

would take all the words in all the languages to begin to describe what composers

really do in the name of music in the late twentieth century) and I trust a

guide that would have much in common with any other list of "themes" (concepts,

ideas, structures, maps, inspirations, aspirations, etc) put forth by any other

living composer of contemporary Western concert music. In my typically "american"

way one can see that my selection of "themes" veers in all directions at once,

like contemporary life itself, like a baby learning to walk. Perhaps today's

music is, in fact, learning to walk for the second or even third time. After

decades of unfulfilled modernist Utopias in an uncertain and violent present,

where some say that "the end of music" looms over the horizon (as does the "End

of History"), we are now confronted with the immense task of handling, storing,

destroying and recycling the massive formless quantity of barely digested matter

(the entirety of the human collective mind), which, while continuing to grow

non-stop, already contains everything that ever was known and is known of our

origins, histories, sciences, geographies, cosmologies, languages, religions,

arts and the musics of all times and places. To this we must add the speculations

about what we will know of of the knowing in the future.

While

only a short generic list, this is a kind of beginner's guide (for surely it

would take all the words in all the languages to begin to describe what composers

really do in the name of music in the late twentieth century) and I trust a

guide that would have much in common with any other list of "themes" (concepts,

ideas, structures, maps, inspirations, aspirations, etc) put forth by any other

living composer of contemporary Western concert music. In my typically "american"

way one can see that my selection of "themes" veers in all directions at once,

like contemporary life itself, like a baby learning to walk. Perhaps today's

music is, in fact, learning to walk for the second or even third time. After

decades of unfulfilled modernist Utopias in an uncertain and violent present,

where some say that "the end of music" looms over the horizon (as does the "End

of History"), we are now confronted with the immense task of handling, storing,

destroying and recycling the massive formless quantity of barely digested matter

(the entirety of the human collective mind), which, while continuing to grow

non-stop, already contains everything that ever was known and is known of our

origins, histories, sciences, geographies, cosmologies, languages, religions,

arts and the musics of all times and places. To this we must add the speculations

about what we will know of of the knowing in the future.

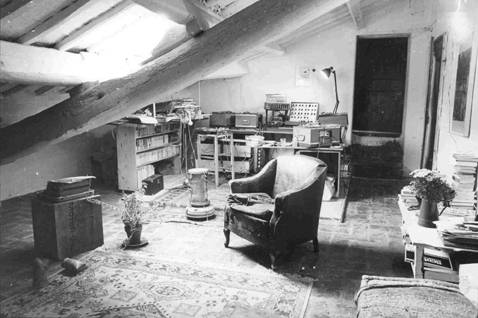

photo Gerd Conrad

I would like, however, to redirect the discourse to those few things I do know something about -- namely my own music -- a music which in its directionless direction and multifarious forms of expression is, after all, just one music of one composer -- and perhaps one whose work might even exemplify the THE NEW COMMON PRACTICE -- Let me further clarify my proposition and give some identity to this amorphous bag of ancient Greek and Latin words listed above. Let's start with a definition: THE NEW COMMON PRACTICE is the direct unmediated embracing of sound, all and any sound, as well as the connecting links between sounds, regardless of their origins, histories or specific meanings; by extension, it is the self guided compositional structuring of any number of sound objects of whatever kind sequentially and/or simultaneously in time and in space with any available means. Here, THE ALL and ONE are equal and interchangeable.

score for Treatise, by Cornelius Cardew

In the brief history of Western Art Music we can safely assume that at any given moment the composers, performers, theorists and public were all in relative agreement about that which they called "the music of their time."

This

music was always based on a set of generally accepted principles and codified

practices -- in Machaut's time as in Mozart's for example, but nonetheless,

all subject to the mysterious laws of human creativity, variation and evolution.

Today for a number of reasons, as complex as contemporary life itself, we in

l994 a.d. no longer have a single codified musical language and practice but

100, 1000, 1..........n, or possibly as many languages as there are composers.

Such has the near exponential and centrifugal expansion of musical languages

developed in the last 100 years. Perhaps the Messiah has already arrived; perhaps

we are already "speaking in tongues" and are not yet aware of it. But however

my illogical fantasy metastisizes, one thing is certain and that is, as my dear

colleague Frederic Rzewski demonstrated at a recent Mills College seminar: today

nobody agrees exactly what music is. This may be or has been true for all times

and places but as far as we know there has never been such an overwhelming amount

of diverse musics existing and employed contemporaneously anywhere before our

present times. Here I am not speaking only about so called new music but all

the musics that fill our concert halls, radios, tv's, airports, streets, shopping

centers, circuses and our lives. In short, I am speaking about the near viral

epidemic and round the clock diffusion of all music of any time and origin.

And we, the composers of the NEW, in our somewhat myopic missionary zeal carry

on our experimental work at the very center of this phenomenon, as in the eye

of the storm, scarcely noticed except by those of our immediate or larger musical

family who instinctively know us by our look, smell and sound. Meanwhile we

scarcely notice the raging storm around us. The NEW COMMON PRACTICE is, in fact,

the inevitable result of our being at last freed of all rules, stylistic conventions,

codes, and even ethics (the recycling of anyones music without their consent

is currently is becoming tacitly legal, through sampling, collage, computer

internets and other means); and hence, free (or condemned as some believe) to

choose as our own any musical path, language or compositional model that has

ever been or will ever be. A kind of Heaven and Hell, ambiguously perched both

in and outside of History, where we operate with little else but our meager

bag of pseudo-scientific words to sustain us and inspire us - like our colleagues

the Particle Physicists - hoping to uncover the ultimate origins of musical

matter and to know its meaning once and for all. HERE, ALL MUSICS SHOULD BE

POSSIBLE, WHERE ARE THEY?

This

music was always based on a set of generally accepted principles and codified

practices -- in Machaut's time as in Mozart's for example, but nonetheless,

all subject to the mysterious laws of human creativity, variation and evolution.

Today for a number of reasons, as complex as contemporary life itself, we in

l994 a.d. no longer have a single codified musical language and practice but

100, 1000, 1..........n, or possibly as many languages as there are composers.

Such has the near exponential and centrifugal expansion of musical languages

developed in the last 100 years. Perhaps the Messiah has already arrived; perhaps

we are already "speaking in tongues" and are not yet aware of it. But however

my illogical fantasy metastisizes, one thing is certain and that is, as my dear

colleague Frederic Rzewski demonstrated at a recent Mills College seminar: today

nobody agrees exactly what music is. This may be or has been true for all times

and places but as far as we know there has never been such an overwhelming amount

of diverse musics existing and employed contemporaneously anywhere before our

present times. Here I am not speaking only about so called new music but all

the musics that fill our concert halls, radios, tv's, airports, streets, shopping

centers, circuses and our lives. In short, I am speaking about the near viral

epidemic and round the clock diffusion of all music of any time and origin.

And we, the composers of the NEW, in our somewhat myopic missionary zeal carry

on our experimental work at the very center of this phenomenon, as in the eye

of the storm, scarcely noticed except by those of our immediate or larger musical

family who instinctively know us by our look, smell and sound. Meanwhile we

scarcely notice the raging storm around us. The NEW COMMON PRACTICE is, in fact,

the inevitable result of our being at last freed of all rules, stylistic conventions,

codes, and even ethics (the recycling of anyones music without their consent

is currently is becoming tacitly legal, through sampling, collage, computer

internets and other means); and hence, free (or condemned as some believe) to

choose as our own any musical path, language or compositional model that has

ever been or will ever be. A kind of Heaven and Hell, ambiguously perched both

in and outside of History, where we operate with little else but our meager

bag of pseudo-scientific words to sustain us and inspire us - like our colleagues

the Particle Physicists - hoping to uncover the ultimate origins of musical

matter and to know its meaning once and for all. HERE, ALL MUSICS SHOULD BE

POSSIBLE, WHERE ARE THEY?

Its is from this perspective that I compose. My music is very simple. It consists of Melody, Harmony, Rhythm, Space, Time and Nature, very much like most of the Western Music that preceeded it. But unlike the music of the past and of other places near and far, where these elements function in precise interelated and codified ways, my compositions utilize these basic musical elements individually as musics themselves -- isolated and very often presented alone, as just melody or just harmony etc. They often appear musically in unpredictable sequences or in independently layered structures where say Harmony, Melody and Rhythm have no plausible connections except those created by chance simultaneities. Occasionally these elements are even presented in their older "interrelated, functionally interdependent" ways as a kind of Hypermusical Gestalt. As these musical "objects" appear, disappear and reappear at different times with varied identities they suggest a multiplicity of meanings. Such purposeful ambiguity is the locus of my musical workplace, my spiritual address.

Connecting

these brief personal observations to my developing thesis of The New Common

Practice, I wish to illustrate these ideas with a few simple musical examples.

The solo piano composition FOR CORNELIUS (1982) is an l8-minute work in three

distinct sections, which in many ways defines many of my past and present musical

interests and objectives. Section I (see example 1) is dominated from the start

by a slow sweeping melody which occasionally twists and jumps in unexpected

ways but somehow regains its solemn poise and balance. Harmonized to a pseudo-Satiesque,

pseudo-waltz, it gives off an odor of some latter day "furniture music." This

is repeated three times "senza expressione." At its conclusion, a totally different

music begins based on a single repeated chord, played in a "strumming-tremolo

style (example 2). To This chord are gradually added new tones in an upward

scalar direction until its harmonic journey is ended when the pianist can no

longer sustain the intensity of the prescribed crescendo to fffff. As this iterative

but additive process is set in motion, constantly alternating patterns of icti

are used to add inner rhythmic structure to this otherwise monotonous gesture

(see example 3). As a natural byproduct, huge waves of sound fill the space.

And within these "waves" one begins to hear things that aren"t really there

-- like ghostly choruses and orchestras. In any case, this section of exhausting

rhythmic intensity is followed by chorale-like ending in 3 part triadic harmony

with constantly shifting tonal centers (example 4). This is a typical ending

signature which I have used in many compositions and improvisations and is in

a style that will be further analyzed here by the music theorist David W. Bernstein

in the latter part of this article. There is nothing new here, as nothing new

will be found in any of my music -- there are only three very different musics

composed on one long musical breath.

Connecting

these brief personal observations to my developing thesis of The New Common

Practice, I wish to illustrate these ideas with a few simple musical examples.

The solo piano composition FOR CORNELIUS (1982) is an l8-minute work in three

distinct sections, which in many ways defines many of my past and present musical

interests and objectives. Section I (see example 1) is dominated from the start

by a slow sweeping melody which occasionally twists and jumps in unexpected

ways but somehow regains its solemn poise and balance. Harmonized to a pseudo-Satiesque,

pseudo-waltz, it gives off an odor of some latter day "furniture music." This

is repeated three times "senza expressione." At its conclusion, a totally different

music begins based on a single repeated chord, played in a "strumming-tremolo

style (example 2). To This chord are gradually added new tones in an upward

scalar direction until its harmonic journey is ended when the pianist can no

longer sustain the intensity of the prescribed crescendo to fffff. As this iterative

but additive process is set in motion, constantly alternating patterns of icti

are used to add inner rhythmic structure to this otherwise monotonous gesture

(see example 3). As a natural byproduct, huge waves of sound fill the space.

And within these "waves" one begins to hear things that aren"t really there

-- like ghostly choruses and orchestras. In any case, this section of exhausting

rhythmic intensity is followed by chorale-like ending in 3 part triadic harmony

with constantly shifting tonal centers (example 4). This is a typical ending

signature which I have used in many compositions and improvisations and is in

a style that will be further analyzed here by the music theorist David W. Bernstein

in the latter part of this article. There is nothing new here, as nothing new

will be found in any of my music -- there are only three very different musics

composed on one long musical breath.

In the recent trio SCHTYX, l992, for Violin, Piano and Percussion, the music encompasses a much broader, richer but apparently less unified set of fundamental musical objects than the tripartite FOR CORNELIUS. Here, odd remnants of all kinds of originally composed music are thrown with abandon into a common cooking pot: childlike melodies -- like the one that opens the piece; long sections of random intersecting minamalist patterns; waltzes ; Ferociously fragmented Post-serial tumult; Passages of Feldmanesque repeated tranquility and warmth; Irish folk songs; improvised explosions of percussion, thrown objects, dog whistles and moving furniture; and a typically harmonic but dissonant hymnlike chorale at the end. This piece is no collage nor is it a virtuoso demonstration of irony. It is, rather, one continuous disjunct text -- a history of chaotic jokes and sublime tendencies -- a kind of portrait of everybody (see examples of last four pages).

In the first 24 minutes of, CRYSTAL PSALMS l988, (See Lowy's "From Fog Horn to Shofar") scored for 7 mixed choruses tape and 6 quartets of: Bass Flutes, Bass Clarinets, Bass Trombones, Viole, Celli, Tubas and Sax each with accordion and percussion, (with each ensemble and Chorus performing independently via Radio from 6 European Capitals) isolated minor triads, melodic fragments and simple percussive rhythms, appear regularly in a number of fixed cycles situated between 41 and 63 seconds long -- like in a miniature Keplerian Universe. While in principle totally predictable, the product of the shifting relationships of these fixed objects creates a most unpredictable series of musical collisions, which momentarly mask their utter and indifferent independence but offer no way out of their eternal state as non-functional orbiting triads.

While so much of my music is thought to derive from the use of natural sounds, electronics and other so-called experimental developments, I am pleased to be able to consider some of my acoustic concert music, through which I reafirm my links to the world community of musical artisans who compose for the simple joy inherent in this art, in particular to those of the great traditions of European, Asian and Afroamerican Art Musics which have so enriched all of our lives. It is clear that the NEW COMMON PRACTICE is, as I intend it, our entire contemporary musical environment, and one which ultimately derives from the increasingly changing and challenging equilibrium between these dominant musical traditions.

Alvin Curran, Mills College

15.III.94

Full article published in German as "Die neue allgemeine Praxis" in Musik Texte issue 53, March 1994. Excerpts published in English as "Reflections of an American Composer in the Late Twentieth Century" (excerpt from The New Common Practice) in Open Space Magazine, issue 3, Spring 2001, pp. 264-67 and in Italian as "La nuova pratica comune: riflessioni di un compositore americano alla fine del ventesimo secolo," in Drammaturgie sonore: Teatri del secondo Novecento, ed. Valentina Valentini, Bulzoni, Rome, 2012, pp. 121-26.